Review: Ballet Black – Mixed Bill – Linbury Studio Theatre, ROH

Reviewed by Graham Watts

EGAL Robert Binet / Dopamine (you make my levels go silly) Ludovic Ondiviela / The One Played Twice Javier De Frutos / War Letters Christopher Marney

A whistle-stop trip to Russia immediately after this show has allowed the rare luxury of the overall scope and flavour of an ambitious quadruple bill of new work to simmer in my consciousness before writing this review. To begin with let’s consider the rarity of that brief statement – a “quadruple bill of new work”: We may not experience such a programme that often but it has now become a hardy spring annual, guaranteed each time Ballet Black opens a new season. No other company comes close to their record of commissioning new work year-on-year, all produced without so much as a postage stamp of state funding whilst there is a strong argument to suggest that here is the one company that truly deserves that support on any number of levels.

One such boon is that their relentless quest for new work has encouraged many choreographers to hone their skills, providing a bridge from their own performance careers to the promising land of making work for others to dance. The quantum of these fortunate people must now have exceeded 20, most of whom have used the Ballet Black commission as a stepping stone to a freelance career. By coincidence, in Russia I met Jonathan Watkins, recently departed from the ranks of The Royal Ballet, in the throes of creating a new work at the Ural Opera House in Yekaterinburg and was reminded that one of his early external commissions was to make a duet for Ballet Black last year.

The company seems to grow by one dancer a year but the current ensemble still only numbers just eight. They are immensely busy delivering a full evening’s programme that has settled into a standard pattern of three brief works utilising each dancer just once before the interval, followed by a more substantial one-act ballet that engages the whole troupe. It’s a necessary formula that works well and, as before, there are no weak links in the chain either choreographically or in terms of the performance outcomes.

First up was a work by Robert Binet, a Canadian now operating as the Royal Ballet’s Choreographic Apprentice under the tutelage of Wayne McGregor. His duet entitled EGAL (a defunct old English word meaning equal) seeks to explore what happens in an encounter of two identical people. The music – Godot by Volker Bertelmann and Hilary Hahn – was challenging for both dancers and audience and Binet’s choreography drew maximum range from this hypothesis of absolute equality. This included complex hand movements performed harmoniously with both dancers rooted to the spot but also a sense of polarisation that drew the dancers together but also kept them apart, as if repelled magnetically. The coupling of Cira Robinson and Jacob Wye was brave but the first-year apprentice acquitted himself well in holding on to Robinson’s dynamic presence and liquid movement. This is one to be seen again.

The next work, entitled Dopamine (you make my levels go silly), continued along a similar path in a duet that also spoke of the heady thrill of physical attraction. Following hot on the heels of Liam Scarlett and Watkins, another young Royal Ballet dancer well down the road towards a choreographic career is Ludovic Ondiviela. In seeking to replicate the neurological impact of the blissful blast of dopamine released in that first flush of mutual, lustful desire, Ondiviela has carved out a strong emotional pas de deux that features another round of fast hand movements and some powerful lifts. Jazmon Voss and Sayaka Ichikawa gave a believable account of a freshly-smitten pair intoxicated by their self-inflicted silly levels of love.

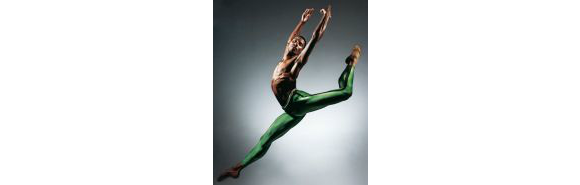

There isn’t a pigeon hole big enough to accommodate the breadth of work by Javier de Frutos and The One Played Twice adds another new dimension to his output. This is a largely joyful suite of dances performed to a half dozen traditional Hawaiian songs, sung in barbershop style, and performed as solos, duets and a quartet. De Frutos draws out both the humour and pathos of these lyrical tunes without ever falling into a hackneyed account of their Polynesian influences. It was a delightful example of simple dance performed with an adventurous joy. The maturity of two established dancers (Sarah Kundi and Damien Johnson) and the refreshing zest of relative newcomers (José Alves and Kanika Carr) worked exceptionally well.

The more substantial work was an exemplar of how to create flavour and attitude through a rough sketch that successfully invokes the mood of an era with no set and without any colouring-in of a detailed narrative. Christopher Marney – who made this work while performing as Count Lilac to great acclaim in Matthew Bourne’s recent Sleeping Beauty – was influenced by letters between a soldier and his fiancée that he saw in the Imperial War Museum. In five scenes, he views the impact of war on relationships from different angles: the soldier dreaming of the girl left behind; an oasis of normality on leave spent in a dance hall – and women awaiting the return of their loved ones following the armistice. Best of all were Robinson’s duet with her “wounded” paramour (Voss) and a haunting dance in which an army greatcoat symbolised Ichikawa’s anguished loss. The costumes (sourced by Gary Harris) gave a flavour of the wartime mentality of make-do-and-mend, a spirit that characterised Marney’s own simple and thrifty approach to conveying his concept economically but with purpose and style.

This was an impressive panoply of dance style and emotion, superbly lit throughout, covering dance for joy, dance that carried the whispery scintilla of an idea and dance that summarised the agony and stolen ecstasies of a generation lost to war. A combination of the enthusiastic rigour of these busy dancers and the ability of their choreographers to shine a light on so much life with such little embellishment gave this evening in the company of Ballet Black a powerful and lasting resonance.